User’s Guide, Chapter 4: Lists, Streams (I) and Output¶

In the last two chapters, I introduced the concept of

Note objects which are made up of

Pitch and

Duration objects, and we even displayed a

Note on a staff and played it via MIDI. But unless you’re challenging

Cage and Webern for the status of least musical material, you will

probably want to analyze, manipulate, or create more than one Note.

Python has ways of working with multiple objects and music21 extends

those ways to be more musical. Let’s look at how Python does it first

and then see how music21 extends these ways. (If you’ve been

programming for a bit, or especially if you have Python experience, skip

to the section on Streams below after creating the objects note1,

note2 and note3 described below).

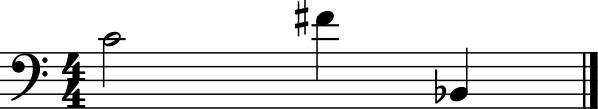

Say you have two notes, a C and an F# in the middle of the treble staff. (If the concept of working with a tritone bothers you, go ahead and make the second note a G; we won’t mind; we’ll just call you Pope Gregory from now on). Lets create those notes:

Working with multiple objects via Lists¶

from music21 import *

note1 = note.Note("C4")

note2 = note.Note("F#4")

Let’s make the first note a half note by modifying its duration (by

default all Note objects are quarter notes):

note1.duration.type = 'half'

note1.duration.quarterLength

2.0

note2.duration.quarterLength

1.0

To print the step (that is, the name without any octave or

accidental information) of each of these notes, you could do something

like this:

print(note1.step)

C

print(note2.step)

F

But suppose you had thirty notes? Then it’d be a pain to type

“print(noteX.step)” thirty times. Fortunately, there’s a solution:

we can put each of the note objects into a List which is a built in

Python object that stores multiple other objects (like Notes or Chords,

or even things like numbers). To create a list in Python, put square

brackets ([]) around the things that you want to put in the list,

separated by commas. Let’s create a list called noteList that

contains note1 and note2:

noteList = [note1, note2]

We can check that noteList contains our Notes by printing it:

print(noteList)

[<music21.note.Note C>, <music21.note.Note F#>]

The list is represented by the square brackets around the end with the comma in between them, just like how they were created originally. The act of creation is mirrored in the representation. That’s nice. Medieval philosophers would approve.

Now we can write a two-line program that will print the step of each

note in noteList. Most modern languages have a way of doing some action

for each member (“element”) in a list (also called an “array” or

sometimes “row”). In Python this is the “for” command. When you type

these lines, make sure to type the spaces at the start of the second

line. (When you’re done typing print(thisNote.step), you’ll probably

have to hit enter twice to see the results.)

for thisNote in noteList:

print(thisNote.step)

C

F

What’s happening here? What for thisNote in noteList: says is that

Python should take each note in noteList in order and temporarily call

that note “thisNote” (you could have it called anything you want;

myNote, n, currentNote are all good names, but note is

not because note is the name of a module). Then the “:” at the end

of the line indicates that everything that happens for a bit will apply

to every Note in noteList one at a time. How does Python know when

“a bit” is over? Simple: every line that is a part of the loop needs to

be indented by putting in some spaces. (I usually use four spaces or hit

tab. Some people use two spaces. Just be consistent.)

Loops don’t save much time here, but imagine if noteList had dozens or hundreds of Notes in it? Then the ability to do something to each object becomes more and more important.

Let’s add another note to noteList. First let’s create another note, a low B-flat:

note3 = note.Note("B-2")

Then we’ll append that note to the end of noteList:

noteList.append(note3)

Lists can be manipulated or changed. They are called “mutable” objects

(we’ll learn about immutable objects later). Streams, as we will see,

can be manipulated the same way through .append().

We can see that the length of noteList is now 3 using the len()

function:

len(noteList)

3

And if we write our looping function again, we will get a third note:

for thisNote in noteList:

print(thisNote.step)

C

F

B

We can find out what the first note of noteList is by writing:

noteList[0]

<music21.note.Note C>

Notice that in a list, the first element is [0], not [1]. There

are all sorts of historical reasons why computers start counting lists

with zero rather than one–some good, some obsolete–but we need to live

with this if we’re going to get any work done. Think of it like how

floors are numbered in European buildings compared to American

buildings. If we go forward one note, to the second note, we write:

noteList[1]

<music21.note.Note F#>

We can also ask noteList where is note2 within it, using the

index() method:

noteList.index(note2)

1

If we want to get the last element of a list, we can write:

noteList[-1]

<music21.note.Note B->

Which is how basements are numbered in Europe as well. This is the same

element as noteList[2] (our third Note), as we can have Python

prove:`

noteList[-1] is noteList[2]

True

Lists will become important tools in your programming, but they don’t

know anything about music. To get some intelligence into our music we’ll

need to know about a music21 object similar to lists, called a

Stream.

Introduction to Streams¶

The Stream object and its subclasses (Score,

Part, Measure) are the fundamental containers for music21 objects such

as Note, Chord,

Clef, TimeSignature

objects.

A container is like a Python list (or an array in some languages).

Objects stored in a Stream are generally spaced in time; each stored object has an offset usually representing how many quarter notes it lies from the beginning of the Stream. For instance in a 4/4 measure of two half notes, the first note will be at offset 0.0, and the second at offset 2.0.

Streams, further, can store other Streams, permitting a wide variety of nested, ordered, and timed structures. These stored streams also have offsets. So if we put two 4/4 Measure objects (subclasses of Stream) into a Part (also a type of Stream), then the first measure will be at offset 0.0 and the second measure will be at offset 4.0.

Commonly used subclasses of Streams include the

Score, Part, and

Measure. It is important to grasp that any

time we want to collect and contain a group of music21 objects, we put

them into a Stream. Streams can also be used for less conventional

organizational structures. We frequently will build and pass around

short-lived, temporary Streams, since doing this opens up a wide variety

of tools for extracting, processing, and manipulating objects on the

Stream. For instance, if you are looking at only notes on beat 2 of any

measure, you’ll probably want to put them into a Stream as well.

A critical feature of music21’s design that distinguishes it from other

music analysis frameworks is that one music21 object can be

simultaneously stored (or, more accurately, referenced) in more than one

Stream. For examples, we might have numerous

Measure Streams contained in a

Part Stream. If we extract a region of this

Part (using the measures() method), we

get a new Stream containing the specified Measures and the contained

notes. We have not actually created new notes within these extracted

measures; the output Stream simply has references to the same objects.

Changes made to Notes in this output Stream will be simultaneously

reflected in Notes in the source Part. There is one limitation though:

the same object should not appear twice in one hierarchical structure of

Streams. For instance, you should not put a note object in both measure

3 and measure 5 of the same piece – it can appear in measure 3 of one

piece and measure 5 of another piece. (For instance, if you wanted to

track a particular note’s context in an original version of a score and

an arrangement). Most users will never need to worry about these

details: just know that this feature lets music21 do some things that no

other software package can do.

Creating simple Streams¶

Objects stored in Streams are called elements and must be some type of Music21Object (don’t worry, almost everything in music21 is a Music21Object, such as Note, Chord, TimeSignature, etc.).

(If you want to put an object that’s not a Music21Object in a Stream,

put it in an ElementWrapper.)

Streams are similar to Python lists in that they hold individual

elements in order. They’re different in that they can only hold

music21 objects such as Notes or Clef

objects. But they’re a lot smarter and more powerful.

To create a Stream you’ll need to type stream.Stream() and assign it

to a variable using the equal sign. Let’s call our Stream stream1:

stream1 = stream.Stream()

Note object lives in a

module called (lowercase) note, the (capital) Stream object

lives in a module called (lowercase) stream. Variable names, like

stream1 can be either uppercase or lowercase, but I tend to use

lowercase variable names (or camelCase like we did with noteList).Note objects we created above

by using the append method of Stream:stream1.append(note1)

stream1.append(note2)

stream1.append(note3)

Of course, this would be a pain to type for hundreds of Notes, so we

could also use the Stream method

repeatAppend() to add a number of

independent, unique copies of the same Note. This creates independent

copies (using Python’s copy.deepcopy function) of the supplied

object, not references.

stream2 = stream.Stream()

n3 = note.Note('D#5') # octave values can be included in creation arguments

stream2.repeatAppend(n3, 4)

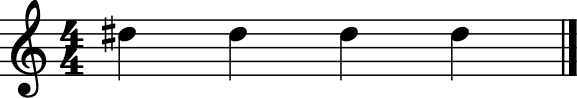

stream2.show()

But let’s worry about that later. Going back to our first stream, we can

see that it has three notes using the same len() function that we

used before:

len(stream1)

3

Alternatively, we can use the show()

method called as show('text') to see what is in the Stream and what

its offset is (here 0.0, since we put it at the end of an empty stream).

stream1.show('text')

{0.0} <music21.note.Note C>

{2.0} <music21.note.Note F#>

{3.0} <music21.note.Note B->

If you’ve setup your environment properly, then calling show with the

musicxml argument should open up Finale, or Sibelius, or MuseScore

or some music notation software and display the notes below.

stream1.show()

Accessing Streams¶

We can also dive deeper into streams. Let’s get the step of each

Note using the for thisNote in ...: command. But now we’ll use

stream1 instead of noteList:

for thisNote in stream1:

print(thisNote.step)

C

F

B

And we can get the first and the last Note in a Stream by using

the [X] form, just like other Python list-like objects:

stream1[0]

<music21.note.Note C>

stream1[-1].nameWithOctave

'B-2'

While full list-like functionality of the Stream isn’t there, some

additional methods familiar to users of Python lists are also available.

The Stream index() method can be used to

get the first-encountered index of a supplied object.

note3Index = stream1.index(note3)

note3Index

2

Given an index, an element from the Stream can be removed with the

pop() method.

stream1.pop(note3Index)

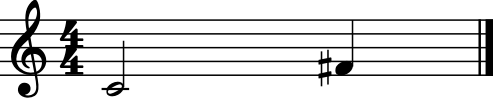

stream1.show()

Since we removed note3 from stream1 with the the

pop() method, let’s add note3 back

into stream1 so that we can continue with the examples below using

stream1 as we originally created it.

stream1.append(note3)

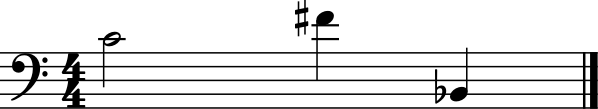

stream1.show()

Separating out elements by class with .getElementsByClass()¶

We can also gather elements based on the class (object type) of the

element, by offset range, or by specific identifiers attached to the

element. Gathering elements from a Stream based on the class of the

element provides a way to filter the Stream for desired types of

objects. The getElementsByClass() method

iterates over a Stream of elements that are instances or subclasses of

the provided classes. The example below gathers all

Note objects and then all

Rest objects. The easiest way to do this is to

use for loops with .getElementsByClass():

for thisNote in stream1.getElementsByClass(note.Note):

print(thisNote, thisNote.offset)

<music21.note.Note C> 0.0

<music21.note.Note F#> 2.0

<music21.note.Note B-> 3.0

If you want instead of passing the class note.Note you could instead

pass the string "Note".

for thisNote in stream1.getElementsByClass('Note'):

print(thisNote, thisNote.offset)

<music21.note.Note C> 0.0

<music21.note.Note F#> 2.0

<music21.note.Note B-> 3.0

It is also possible to pass in a list of classes or strings of class

names to .getElementsByClass() which will return anything that

matches any of the classes. Notice the [] marks in the next call,

indicating that we are creating a list to pass to

.getElementsByClass():

for thisNote in stream1.getElementsByClass(['Note', 'Rest']):

print(thisNote, thisNote.offset)

<music21.note.Note C> 0.0

<music21.note.Note F#> 2.0

<music21.note.Note B-> 3.0

Since there are no note.Rest objects, it’s the same as above. Oh

well…

music21 has a couple of shortcuts that are equivalent to

.getElementsByClass. For instance .notes is equivalent to

.getElementsByClass(['Note', 'Chord']) (we’ll get to chords soon):

for thisNote in stream1.notes:

print(thisNote)

<music21.note.Note C>

<music21.note.Note F#>

<music21.note.Note B->

And .notesAndRests is equivalent to

.getElementsByClass(['Note', 'Chord', 'Rest']).

for thisNote in stream1.notesAndRests:

print(thisNote)

<music21.note.Note C>

<music21.note.Note F#>

<music21.note.Note B->

Finally, there’s something slightly different. .pitches begins with

a call to .notes, but then returns a list of all the pitches from

every Note or Chord in the Stream:

listOut = stream1.pitches

listOut

[<music21.pitch.Pitch C4>,

<music21.pitch.Pitch F#4>,

<music21.pitch.Pitch B-2>]

The result of a .getElementsByClass are not technically streams, but

you can convert it to a stream with .stream() and then call

.show() on it:

sIterator = stream1.getElementsByClass(note.Note)

sOut = sIterator.stream()

sOut.show('text')

{0.0} <music21.note.Note C>

{2.0} <music21.note.Note F#>

{3.0} <music21.note.Note B->

Separating out elements by offset with .getElementsByOffset()¶

The getElementsByOffset() method returns

a Stream of all elements that fall either at a single offset or within a

range of two offsets provided as an argument. In both cases a Stream is

returned.

sOut = stream1.getElementsByOffset(3)

len(sOut)

1

sOut[0]

<music21.note.Note B->

Like with .getElementsByClass() if you want a Stream from

.getElementsByOffset(), add .stream() to the end of it.

sOut = stream1.getElementsByOffset(2, 3).stream()

sOut.show('text')

{2.0} <music21.note.Note F#>

{3.0} <music21.note.Note B->

We will do more with .getElementsByOffset() later when we also talk

about getElementAtOrBefore() and

getElementAfterElement()

More Stream Features¶

Okay, so far we’ve seen that Streams can do the same things as

lists, but can they do more? Let’s call the analyze method on stream to

get the ambitus (that is, the range from the lowest note to the highest

note) of the Notes in the Stream:

stream1.analyze('ambitus')

<music21.interval.Interval A12>

Let’s take a second to check this. Our lowest note is note3 (B-flat

in octave 2) and our highest note is note2 (F-sharp in octave 4).

From B-flat to the F-sharp above it, is an augmented fifth. An augmented

fifth plus an octave is an augmented twelfth. So we’re doing well so

far. (We’ll get to other things we can analyze in chapter 18 and we’ll

see what an Interval object can do in

chapter 15).

As we mentioned earlier, when placed in a Stream, Notes and other elements also have an offset (stored in .offset) that describes their position from the beginning of the stream. These offset values are also given in quarter-lengths (QLs).

Once a Note is in a Stream, we can ask for the offset of the

Notes (or anything else) in it. The offset is the position of a

Note relative to the start of the Stream measured in quarter notes.

So note1’s offset will be 0.0, since it’s at the start of the Stream:

note1.offset

0.0

note2’s offset will be 2.0, since note1 is a half note, worth

two quarter notes:

note2.offset

2.0

And note3, which follows the quarter note note2 will be at

offset 3.0:

note3.offset

3.0

(If we made note2 an eighth note, then note3’s offset would be

the floating point [decimal] value 2.5. But we didn’t.) So now when

we’re looping we can see the offset of each note. Let’s print the note’s

offset followed by its name by putting .offset and .name in the same

line, separated by a comma:

for thisNote in stream1:

print(thisNote.offset, thisNote.name)

0.0 C

2.0 F#

3.0 B-

(Digression: It’s probably not too early to learn that a safer form

of .offset is .getOffsetBySite(stream1):

note2.offset

2.0

note2.getOffsetBySite(stream1)

2.0

What’s the difference? Remember how I said that .offset refers to

the number of quarter notes that the Note is from the front of a

Stream? Well, eventually you may put the same Note in different

places in multiple Streams, so the .getOffsetBySite(X) command

is a safer way that specifies exactly which Stream we are talking about.

End of digression…)

As a final note about offsets, the

lowestOffset property returns the

minimum of all offsets for all elements on the Stream.

stream1.lowestOffset

0.0

So, what else can we do with Streams? Like Note objects, we can

show() them in a couple of different ways. Let’s hear these three

Notes as a MIDI file:

stream1.show('midi')

Or let’s see them as a score:

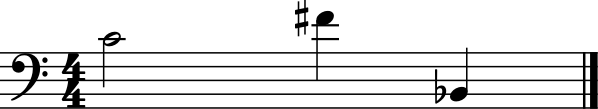

stream1.show()

You might ask why is the piece in common-time (4/4)? This is just the

default for new pieces, which is in the defaults module:

defaults.meterNumerator

4

defaults.meterDenominator

'quarter'

(Some of these examples use a system that automatically tries to get an

appropriate time signature and appropriate clef; in this case,

music21 figured out that that low B-flat would be easier to see in

bass clef than treble.)

We’ll learn how to switch the TimeSignature

soon enough.

If you don’t have MIDI or MusicXML configured yet (we’ll get to it in a

second) and you don’t want to have other programs open up, you can show

a Stream in text in your editor:

stream1.show('text')

{0.0} <music21.note.Note C>

{2.0} <music21.note.Note F#>

{3.0} <music21.note.Note B->

This display shows the offset for each element (that is, each object

in the Stream) along with what class it is, and a little bit more

helpful information. The information is the same as what’s called the

__repr__ (representation) of the object, which is what you get if

you type its variable name at the prompt:

note1

<music21.note.Note C>

By the way, Streams have a __repr__ as well:

stream1

<music21.stream.Stream 0x116b27dc0>

that number at the end is the hex form of the .id of the Stream,

which is a way of identifying it. Often the .id of a Stream will be

the name of the Part (“Violin II”), but if it’s undefined then a

somewhat random number is used (actually the location of the Stream in

your computer’s memory). We can change the .id of a Stream:

stream1.id = 'some_notes'

stream1

<music21.stream.Stream some_notes>

We could have also changed the .id of any of our Note objects,

but it doesn’t show up in the Note’s __repr__:

note1.id = 'my_favorite_C'

note1

<music21.note.Note C>

Now, a Stream is a Music21Object just like

a Note is. This is why it has an .id attribute and, more

importantly, why you can call .show() on it.

What else makes a Music21Object what it is? It has a .duration

attribute which stores a Duration object:

stream1.duration

<music21.duration.Duration 4.0>

stream1.duration.type

'whole'

stream1.duration.quarterLength

4.0

(Notice that the len() of a Stream, which stands for “length”,

is not the same as the duration. the len() of a Stream is the number

of objects stored in it, so len(stream1) is 3).

A related concept to the .duration of a Stream is its

.highestTime, which is the time at which the latest element in the

Stream ends. Usually this is the last element of the stream’s

.offset plus its .quarterLength.

stream1.highestTime

4.0

Streams within Streams¶

And, as a Music21Object, a Stream can be placed inside of

another Stream object. Let’s create a stream, called biggerStream

(for reasons that will become obvious), that holds a Note D# at the

beginning

biggerStream = stream.Stream()

note2 = note.Note("D#5")

biggerStream.insert(0, note2)

Now we use the .append functionality to put stream1 at the end

of biggerStream:

biggerStream.append(stream1)

Notice that when we call .show('text') on biggerStream, we see not

only the presence of note2 and stream1 but also all the contents

of stream1 as well:

biggerStream.show('text')

{0.0} <music21.note.Note D#>

{1.0} <music21.stream.Stream some_notes>

{0.0} <music21.note.Note C>

{2.0} <music21.note.Note F#>

{3.0} <music21.note.Note B->

Notice though that the offsets, the little numbers inside curly

brackets, for the elements of stream1 (“some notes”) relate only to

their positions within stream1, not to their position within

biggerStream. This is because each Music21Object knows its

offset only in relation to its containing Stream, not necessarily to

the Stream containing that Stream.

Also notice that note1 knows that it is in stream1 but doesn’t

know that it is somewhere inside biggerStream:

note1 in stream1

True

note1 in biggerStream

False

All this might not seem like much of a big deal, until we tell you that

in music21, Scores are made up of Streams within Streams

within Streams. So if you have an orchestral score, it is a

Stream, and the viola part is a Stream in that Stream, and

measure 5 of the viola part is a Stream within that Stream, and,

if there were a ‘’divisi’‘, then each’‘diviso’’ voice would be a

Stream within that Stream. Each of these Streams has a

special name and its own class (Score,

Part, Measure, and

Voice), but they are all types of

Streams.

So how do we find note1 inside biggerStream? That’s what the

next two chapters are about.

Chapter 5 covers Lists of Lists. Those with programming experience who have familiarity with lists of lists and defining functions might want to skip to Chapter 6 Streams of Streams.