SymPy User’s Guide¶

Introduction¶

If you are new to SymPy, start with the Tutorial. If you went through it, now it’s time to learn how SymPy works internally, which is what this guide is about. Once you grasp the ideas behind SymPy, you will be able to use it effectively and also know how to extend it and fix it. You may also be just interested in SymPy Modules Reference.

Learning SymPy¶

Everyone has different ways of understanding the code written by others.

Ondřej’s approach¶

Let’s say I’d like to understand how x + y + x works and how it is possible

that it gets simplified to 2*x + y.

I write a simple script, I usually call it t.py (I don’t remember anymore

why I call it that way):

from sympy.abc import x, y

e = x + y + x

print e

And I try if it works

$ python t.py y + 2*x

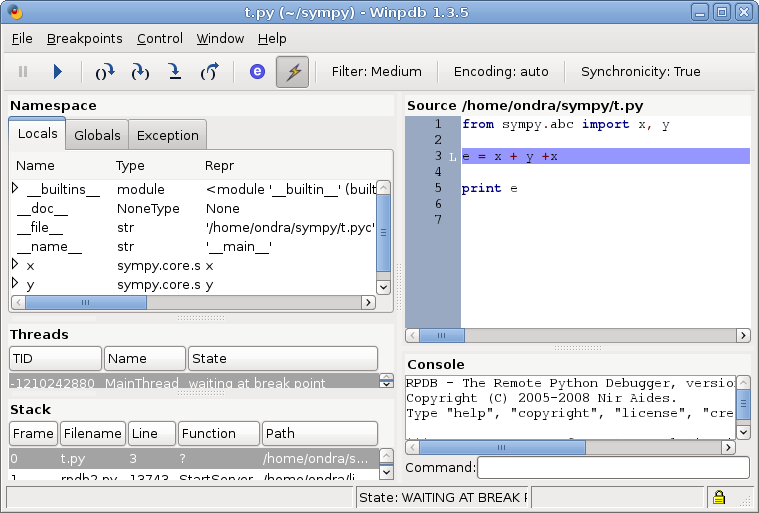

Now I start winpdb on it (if you’ve never used winpdb – it’s an excellent multiplatform debugger, works on Linux, Windows and Mac OS X):

$ winpdb t.py y + 2*x

and a winpdb window will popup, I move to the next line using F6:

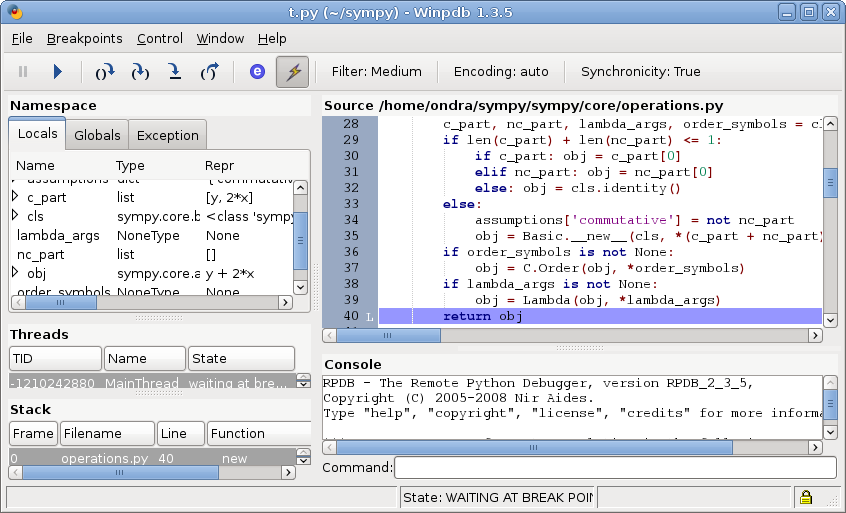

Then I step into (F7) and after a little debugging I get for example:

Tip

Make the winpdb window larger on your screen, it was just made smaller to fit in this guide.

I see values of all local variables in the left panel, so it’s very easy to see

what’s happening. You can see, that the y + 2*x is emerging in the obj

variable. Observing that obj is constructed from c_part and nc_part

and seeing what c_part contains (y and 2*x). So looking at the line

28 (the whole line is not visible on the screenshot, so here it is):

c_part, nc_part, lambda_args, order_symbols = cls.flatten(map(_sympify, args))

you can see that the simplification happens in cls.flatten. Now you can set

the breakpoint on the line 28, quit winpdb (it will remember the breakpoint),

start it again, hit F5, this will stop at this breakpoint, hit F7, this will go

into the function Add.flatten():

@classmethod

def flatten(cls, seq):

"""

Takes the sequence "seq" of nested Adds and returns a flatten list.

Returns: (commutative_part, noncommutative_part, lambda_args,

order_symbols)

Applies associativity, all terms are commutable with respect to

addition.

"""

terms = {} # term -> coeff

# e.g. x**2 -> 5 for ... + 5*x**2 + ...

coeff = S.Zero # standalone term

# e.g. 3 + ...

lambda_args = None

order_factors = []

while seq:

o = seq.pop(0)

and then you can study how it works. I am going to stop here, this should be enough to get you going – with the above technique, I am able to understand almost any Python code.

SymPy’s Architecture¶

We try to make the sources easily understandable, so you can look into the sources and read the doctests, it should be well documented and if you don’t understand something, ask on the mailinglist.

You can find all the decisions archived in the issues, to see rationale for doing this and that.

Basics¶

All symbolic things are implemented using subclasses of the Basic class.

First, you need to create symbols using Symbol("x") or numbers using

Integer(5) or Float(34.3). Then you construct the expression using any

class from SymPy. For example Add(Symbol("a"), Symbol("b")) gives an

instance of the Add class. You can call all methods, which the particular

class supports.

For easier use, there is a syntactic sugar for expressions like:

cos(x) + 1 is equal to cos(x).__add__(1) is equal to

Add(cos(x), Integer(1))

or

2/cos(x) is equal to cos(x).__rdiv__(2) is equal to

Mul(Rational(2), Pow(cos(x), Rational(-1))).

So, you can write normal expressions using python arithmetics like this:

a = Symbol("a")

b = Symbol("b")

e = (a + b)**2

print e

but from the SymPy point of view, we just need the classes Add, Mul,

Pow, Rational, Integer.

Automatic evaluation to canonical form¶

For computation, all expressions need to be in a

canonical form, this is done during the creation of the particular instance

and only inexpensive operations are performed, necessary to put the expression

in the

canonical form. So the canonical form doesn’t mean the simplest possible

expression. The exact list of operations performed depend on the

implementation. Obviously, the definition of the canonical form is arbitrary,

the only requirement is that all equivalent expressions must have the same

canonical form. We tried the conversion to a canonical (standard) form to be

as fast as possible and also in a way so that the result is what you would

write by hand - so for example b*a + -4 + b + a*b + 4 + (a + b)**2 becomes

2*a*b + b + (a + b)**2.

Whenever you construct an expression, for example Add(x, x), the

Add.__new__() is called and it determines what to return. In this case:

>>> from sympy import Add

>>> from sympy.abc import x

>>> e = Add(x, x)

>>> e

2*x

>>> type(e)

<class 'sympy.core.mul.Mul'>

e is actually an instance of Mul(2, x), because Add.__new__()

returned Mul.

Comparisons¶

Expressions can be compared using a regular python syntax:

>>> from sympy.abc import x, y

>>> x + y == y + x

True

>>> x + y == y - x

False

We made the following decision in SymPy: a = Symbol("x") and another

b = Symbol("x") (with the same string “x”) is the same thing, i.e. a == b is

True. We chose a == b, because it is more natural - exp(x) == exp(x) is

also True for the same instance of x but different instances of exp,

so we chose to have exp(x) == exp(x) even for different instances of x.

Sometimes, you need to have a unique symbol, for example as a temporary one in

some calculation, which is going to be substituted for something else at the

end anyway. This is achieved using Dummy("x"). So, to sum it

up:

>>> from sympy import Symbol, Dummy

>>> Symbol("x") == Symbol("x")

True

>>> Dummy("x") == Dummy("x")

False

Debugging¶

Starting with 0.6.4, you can turn on/off debug messages with the environment

variable SYMPY_DEBUG, which is expected to have the values True or False. For

example, to turn on debugging, you would issue:

[user@localhost]: SYMPY_DEBUG=True ./bin/isympy

Functionality¶

There are no given requirements on classes in the library. For example, if they

don’t implement the fdiff() method and you construct an expression using

such a class, then trying to use the Basic.series() method will raise an

exception of not finding the fdiff() method in your class. This “duck

typing” has an advantage that you just implement the functionality which you

need.

You can define the cos class like this:

class cos(Function):

pass

and use it like 1 + cos(x), but if you don’t implement the fdiff() method,

you will not be able to call (1 + cos(x)).series().

The symbolic object is characterized (defined) by the things which it can do,

so implementing more methods like fdiff(), subs() etc., you are creating

a “shape” of the symbolic object. Useful things to implement in new classes are:

hash() (to use the class in comparisons), fdiff() (to use it in series

expansion), subs() (to use it in expressions, where some parts are being

substituted) and series() (if the series cannot be computed using the

general Basic.series() method). When you create a new class, don’t worry

about this too much - just try to use it in your code and you will realize

immediately which methods need to be implemented in each situation.

All objects in sympy are immutable - in the sense that any operation just

returns a new instance (it can return the same instance only if it didn’t

change). This is a common mistake to change the current instance, like

self.arg = self.arg + 1 (wrong!). Use arg = self.arg + 1; return arg instead.

The object is immutable in the

sense of the symbolic expression it represents. It can modify itself to keep

track of, for example, its hash. Or it can recalculate anything regarding the

expression it contains. But the expression cannot be changed. So you can pass

any instance to other objects, because you don’t have to worry that it will

change, or that this would break anything.

Conclusion¶

Above are the main ideas behind SymPy that we try to obey. The rest

depends on the current implementation and may possibly change in the future.

The point of all of this is that the interdependencies inside SymPy should be

kept to a minimum. If one wants to add new functionality to SymPy, all that is

necessary is to create a subclass of Basic and implement what you want.

Functions¶

How to create a new function with one variable:

class sign(Function):

nargs = 1

@classmethod

def eval(cls, arg):

if isinstance(arg, Basic.NaN):

return S.NaN

if isinstance(arg, Basic.Zero):

return S.Zero

if arg.is_positive:

return S.One

if arg.is_negative:

return S.NegativeOne

if isinstance(arg, Basic.Mul):

coeff, terms = arg.as_coeff_mul()

if not isinstance(coeff, Basic.One):

return cls(coeff) * cls(Basic.Mul(*terms))

is_finite = True

def _eval_conjugate(self):

return self

def _eval_is_zero(self):

return isinstance(self[0], Basic.Zero)

and that’s it. The _eval_* functions are called when something is needed.

The eval is called when the class is about to be instantiated and it

should return either some simplified instance of some other class or if the

class should be unmodified, return None (see core/function.py in

Function.__new__ for implementation details). See also tests in

sympy/functions/elementary/tests/test_interface.py that test this interface. You can use them to create your own new functions.

The applied function sign(x) is constructed using

sign(x)

both inside and outside of SymPy. Unapplied functions sign is just the class

itself:

sign

both inside and outside of SymPy. This is the current structure of classes in SymPy:

class BasicType(type):

pass

class MetaBasicMeths(BasicType):

...

class BasicMeths(AssumeMeths):

__metaclass__ = MetaBasicMeths

...

class Basic(BasicMeths):

...

class FunctionClass(MetaBasicMeths):

...

class Function(Basic, RelMeths, ArithMeths):

__metaclass__ = FunctionClass

...

The exact names of the classes and the names of the methods and how they work can be changed in the future.

This is how to create a function with two variables:

class chebyshevt_root(Function):

nargs = 2

@classmethod

def eval(cls, n, k):

if not 0 <= k < n:

raise ValueError("must have 0 <= k < n")

return cos(S.Pi*(2*k + 1)/(2*n))

Note

the first argument of a @classmethod should be cls (i.e. not

self).

Here it’s how to define a derivative of the function:

>>> from sympy import Function, sympify, cos

>>> class my_function(Function):

... nargs = 1

...

... def fdiff(self, argindex = 1):

... return cos(self.args[0])

...

... @classmethod

... def eval(cls, arg):

... arg = sympify(arg)

... if arg == 0:

... return sympify(0)

So guess what this my_function is going to be? Well, it’s derivative is

cos and the function value at 0 is 0, but let’s pretend we don’t know:

>>> from sympy import pprint

>>> pprint(my_function(x).series(x, 0, 10))

3 5 7 9

x x x x / 10\

x - -- + --- - ---- + ------ + O\x /

6 120 5040 362880

Looks familiar indeed:

>>> from sympy import sin

>>> pprint(sin(x).series(x, 0, 10))

3 5 7 9

x x x x / 10\

x - -- + --- - ---- + ------ + O\x /

6 120 5040 362880

Let’s try a more complicated example. Let’s define the derivative in terms of the function itself:

>>> class what_am_i(Function):

... nargs = 1

...

... def fdiff(self, argindex = 1):

... return 1 - what_am_i(self.args[0])**2

...

... @classmethod

... def eval(cls, arg):

... arg = sympify(arg)

... if arg == 0:

... return sympify(0)

So what is what_am_i? Let’s try it:

>>> pprint(what_am_i(x).series(x, 0, 10))

3 5 7 9

x 2*x 17*x 62*x / 10\

x - -- + ---- - ----- + ----- + O\x /

3 15 315 2835

Well, it’s tanh:

>>> from sympy import tanh

>>> pprint(tanh(x).series(x, 0, 10))

3 5 7 9

x 2*x 17*x 62*x / 10\

x - -- + ---- - ----- + ----- + O\x /

3 15 315 2835

The new functions we just defined are regular SymPy objects, you can use them all over SymPy, e.g.:

>>> from sympy import limit

>>> limit(what_am_i(x)/x, x, 0)

1

Common tasks¶

Please use the same way as is shown below all across SymPy.

accessing parameters:

>>> from sympy import sign, sin

>>> from sympy.abc import x, y, z

>>> e = sign(x**2)

>>> e.args

(x**2,)

>>> e.args[0]

x**2

Number arguments (in Adds and Muls) will always be the first argument;

other arguments might be in arbitrary order:

>>> (1 + x + y*z).args[0]

1

>>> (1 + x + y*z).args[1] in (x, y*z)

True

>>> (y*z).args

(y, z)

>>> sin(y*z).args

(y*z,)

Never use internal methods or variables, prefixed with “_” (example: don’t

use _args, use .args instead).

testing the structure of a SymPy expression

Applied functions:

>>> from sympy import sign, exp, Function

>>> e = sign(x**2)

>>> isinstance(e, sign)

True

>>> isinstance(e, exp)

False

>>> isinstance(e, Function)

True

So e is a sign(z) function, but not exp(z) function.

Unapplied functions:

>>> from sympy import sign, exp, FunctionClass

>>> e = sign

>>> f = exp

>>> g = Add

>>> isinstance(e, FunctionClass)

True

>>> isinstance(f, FunctionClass)

True

>>> isinstance(g, FunctionClass)

False

>>> g is Add

True

So e and f are functions, g is not a function.

Contributing¶

We welcome every SymPy user to participate in it’s development. Don’t worry if you’ve never contributed to any open source project, we’ll help you learn anything necessary, just ask on our mailinglist.

Don’t be afraid to ask anything and don’t worry that you are wasting our time if you are new to SymPy and ask questions that maybe most of the people know the answer to – you are not, because that’s exactly what the mailinglist is for and people answer your emails because they want to. Also we try hard to answer every email, so you’ll always get some feedback and pointers what to do next.

Improving the code¶

Go to issues that are sorted by priority and simply find something that you would like to get fixed and fix it. If you find something odd, please report it into issues first before fixing it. Feel free to consult with us on the mailinglist. Then send your patch either to the issues or the mailinglist.

Please read our excellent SymPy Patches Tutorial at our wiki for a guide on how to write patches to SymPy, how to work with Git, and how to make your life easier as you get started with SymPy.

Improving the docs¶

Please see the documentation how to fix and improve SymPy’s documentation. All contribution is very welcome.